Today in the UK is what we call Remembrance Day. At the 11th hour on the 11th hour of the 11th month we stop to stand in silence for two minutes in remembrance of the dead of wars. This day I have been thinking of my own father. He died, not in the war, but 41 years ago as a result of the illnesses he suffered as a result of the treatment he received in the Second War as a prisoner of war of the Japanese.

It also brought to mind a very memorable trip I made to Belarus in 2012. This piece is about part of that visit.

This is the signpost by the side

of the road 100 kms north east of Minsk for the village of Khatyn. The village lies another 4 kms along a gentle

forest road and does nothing to prepare you for what you see there. The current village is a monument to the destruction of many many villages of Belarus which was carried out during World War Two, or The Great Patriotic War, as the Russians call it.

The village of Khatyn is one of several hundred Belarussian villages which were burned to the

ground, flattened and the people murdered by the Nazis during the period from

1941-1945. Over 2 million Belarussians died during that period, not only in

the villages but the towns as well.

One in four of the entire

population were killed. One in four. Think about that a moment.

The capital city of Minsk did not regain it's pre-war

population figures until 1971. Today the country still has not regained

its pre-war population figures.

There is a net loss of population going on.

Khatyn (not to be confused with Katyn near Smolensk in Russia - the place

where 12,000 Polish officers and intelligentsia were murdered) is a monument built on

the footprint of the original village.

The entire population were herded

into a large barn and the barn set fire to. Those trying to escape were shot, as were others who had

managed to get out of the village. One man from the village lived.

He had been out of the village when the 'action' started. He is

ccommemorated with a larger than life statue at the entrance to the whole site.

Where the villagers houses stood

is a concrete outline of the house together with a replica of the chimney.

Set into the top of the chimney is a bell. The bells toll during

the daylight hours to remind visitors of those who had died. In the

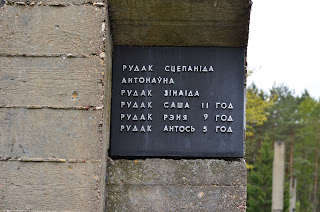

entrance to the houses is a grey slate plaque with the names of those people

from the house who were killed. Some were as young as three weeks

old.

The image above is one of many at the site. It is a chimney stack with a small bell on its top. As you walk around the site you can hear the sound of the bell tolling every few seconds, a low melancholy sound. It is mean to represent the death of one person from Belarus during the war. On the front of the chimney are grey slate plaques. They are inscribed with the names of the people from the house which was on the site who were killed. In the image below you can see the names of a mother and father, together with the names of their three children, aged 11, 9 and 5.

This is the statue of the one surviving man, carrying the dead body of his son from the village. As you can see, children are encouraged not only to remember those who died, but to respect them as well.

Each of the stone monuments is to represent a Belarussian village destroyed, together with its name.